Design Matters #8 - What The Font?!

- Thabata Romanowski

- Sep 9, 2024

- 10 min read

This is a repost of the Design Matters series I run as part of my newsletter, originally sent to my subscribers on 01 September 2023.

If you'd like what you read, consider subscribing so you can get all upcoming issues fresh when they're first out!

Hi Friends!

Welcome to issue #8 of the series Design Matters.

In this series, I’ll share with you how design can help your dashboards go from average to awesome.

The goal of this series is to shed light on how design plays an indispensable role in data analytics - not just in making things look pretty but in affecting understanding, communication, and decision-making.

Last week, I talked about how colour. If you haven't got the chance to read it, you can check it out in the archive, along with all previous Design Matters issues.

Data Visualisation is about communication. We usually focus a lot of time talking about the shapes we choose to use, the colours we’ll apply to them, and how to place elements best on screen. But there is an often forgotten element that can make or break your design. Typography.

Maybe it’s because, unlike with design tools, BI tools don’t allow for modifications and tweaks when it comes to fonts. Perhaps it’s because marketing and branding departments make visual guidelines choices and apply them to all internal communications - and with that, type choices are already made, even if they don’t fit well with data displays.

Whatever the reason, we see little about how typography is one of the most important elements in a dashboard when it comes to enabling its primary function - communication.

And if you think this is designer talk and typography doesn’t matter that much, just have a look at what we’re left with if we remove all typography from our dashboard mockup from last week:

Even if we don’t give it much thought, text makes some of the most informative elements in a dashboard: the numbers. They are type, too. With them, we have functions like KPIs, comparators, table values, labels, and axis markers.

So today, I’ll give you a primer about the typography concepts that I most use when developing dashboards and what makes a good dataviz typeface.

Typography Semantics

I believe that learning terms and definitions in design can help us a lot because it enables us to articulate our decisions better. In the same way I did with colour, I’ll start by explaining the basic concepts and terms I’ll refer to every time I talk about typography. It is a rather technical and detailed field, so it has lots of specific terms. This is just a brief list of the things I believe affect dataviz designers the most.

1. Typeface or Font

These two terms are often used interchangeably, but they are different. A Typeface is a set of characters developed to be used together in harmony. Arial is a typeface, as is Times New Roman.

A Font is a specific form in which a typeface is delivered. Arial Light, 12pt, is a font. Times New Roman, Regular, Italic, 16pt is a font.

So, when you look at someone’s work, and you like how they chose a collection of different fonts (sizes, weights, sometimes even more than one type family), you can say that you like their “typeface choices”. But if you want to request a particular functional adjustment, you can say, “The font you used for the headers, make them a little bit bigger”.

2. Varying a typeface

When you download a typeface, you may see that there are multiple versions you can choose from. They can be Light, Bold, Black, Regular, Medium, and so on. What you are looking at is a type family - a collection of variations of the same typeface.

There are two fundamental ways you can vary a font - using weight and size.

Weight is the thickness of the lines used in a font. Usually defined by words like Thin, Light, Regular, Medium, Semibold, Bold, Extrabold and Black.

A font can also vary by slant. And when we slant a font, we call it italics. Italics can exist in any font-weight.

A well-designed typeface usually makes small adjustments in their italicised versions to make them look and feel more fluid.

Size is the variation in the height of a character, usually measured in Points (pt) - although some tools let you adjust this in Pixels (px). Beware, pt and px are different measures! A font in 16px is not the same as a font in 16pt.

This happens because points are a physical measure - one Point measures 0.352778 millimetres (or 0.0138889 inches), and it will always measure that. A Pixel, on the other hand, varies in size, depending on screen resolution.

That’s why 24 pixels on a 4K screen look really tiny, but not on a 1080p screen. Your BI tools, like Tableau and Power BI, measure font sizes in Points. But they do so on a screen.

And if you work in conjunction with tools like Figma or Illustrator, you’ll get sizing differences because tools meant for screen design consider font sizes in Pixels. For example, 16pt is roughly 22px. Here’s a neat converter.

All you need to know for now is that, for simplicity’s sake, when I talk about font size for dashboards (created in BI tools), I’ll be talking about Points.

3. To serif or not to serif

Serifs are the little feet or swooshes supporting the letters in your typeface. Typeface kinds are normally split into serif and sans serif (or, without serifs, often referred to as just sans). Times New Roman is a serif typeface. Arial is a sans-serif typeface. Comic Sans? It’s in the name. No serifs.

As a general rule of thumb, serif fonts are better for long-form text, as the little feet get our eyes in a reading flow - connecting one letter to the next and making spaces between them very obvious.

Sans serif fonts are great for labels, signs, and very small font sizes - as their clean look makes the other parts of the letters more easily recognisable. For work involving data, sans-serif fonts are usually my go-to. Serifs have their place, though, and we’ll explore some examples soon.

4. Other anatomical elements of a typeface

There are many things that compose a glyph (a letter or symbol) in a typeface. But we’ll focus on the ones that affect readability when it comes to dataviz. These are the x-height and the counter.

The X-height is the height of the body of the typeface - that is, the height of the letter like a lowercase e, a, o. This is done because of two other parts of the typeface: the ascenders - the arms that go up in letters like t and the dots of the i - and descenders - the legs of letters like p, q and y.

A good X-height for readability is a bigger one - this means that a typeface is more readable if the body of the letters is proportionally bigger in relation to its ascenders and descenders, especially at smaller sizes. We’ll soon explore a few examples of that.

Counter is the same as the inside part of the round shapes of letters like lowercase o and a. In a letter like e, the internal round bit can be called an eye.

The relationship between these two elements helps us determine how legible a typeface can be at different sizes. Mixing similar counter shapes and x-heights of different letters is what your optometrist does to test your eyesight. How many times have you confused a p, a q and an a in your eye tests? And it does get harder the smaller it gets, doesn’t it? The same happens with your dataviz when you make poor typeface choices.

5. A note on condensed fonts

You may be tempted, for either space-saving or aesthetic reasons, to use a narrower or condensed typeface. These are the typefaces that have a smaller width and a bigger height.

This also means that their counters are vertically stretched, making it a bit more difficult to tell your a from your o, especially at smaller sizes. For dataviz, it can be tempting to use a condensed typeface to make longer labels fit within the limits of our charts, but as we’ll explore in a few examples when it comes to legibility - mainly of data and axis labels, regular width is best, even if you need to reduce the font size a bit for it to fit.

Generally, for the sake of readability and accessibility, go for a regular width with a generous X-height.

6. Numbers

There are a few basic styles of numbers in typefaces. Sometimes, the same typeface may give you more than one number option.

Oldstyle numbers make sense when you’re reading long texts. They are numbers that go up and down from the baseline upper line of your typeface. Commas and other symbols also vary in vertical placement along numbers.

Lining numbers align with the baseline of your chosen typeface. In the example below, we can see the same typeface (Georgia, a serif typeface) with different number options. Oldstyle above, Lining below.

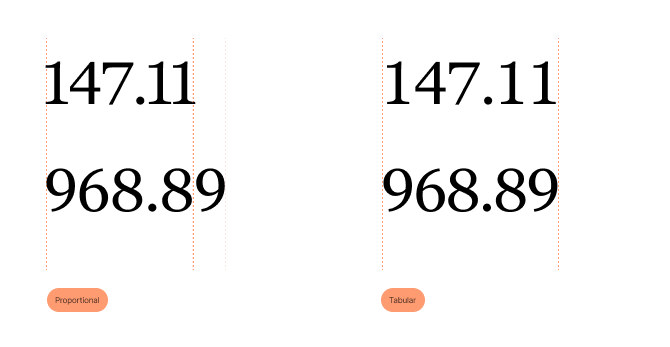

Another stylistic consideration for numbers is whether they are proportional or tabular.

Proportional numbers mean that each number will have a different width, depending on how much space they need - which makes sense when writing long texts; you’d want your 1 to occupy less space than your 8, for example.

But when talking about Tables, what usually matters most is to quickly tell if your number has 2 digits or 4. For these cases, there are tabular numbers - where all numbers have the same width. So, whether you are displaying 147.11 or 968.89, the width occupied by both numbers will be the same.

Tabular numbers also make great KPIs, as we intuitively align them when they’re of similar sizes.

7. Symbols

Another often overlooked aspect when discussing typefaces is choosing one that contains all the symbols we may need in our visualisation while ensuring they are not overly stylised.

For example, you may want to use percentages (%), mathematical symbols (+ -, ^) or superscript numbers. Some typefaces may not contain certain currency symbols. Make sure you’re well covered.

Another thing to take into consideration is the style of such symbols. Is the percentage sign easily recognisable? Is the typeface trying to be clever or too minimalistic with the currency glyphs? Remember that your purpose is to communicate as easily as possible, not to confuse your audience.

Of course, if you’re one to make use of other symbols like arrows, for example, you may want to have access to a symbols-only typeface - they can be quite handy! Check this neat video about the origins of Wingdings to see what I mean.

Now that we have all the terms covered, we can go forth and conquer.

Functional Typography

Much like colour, the best way to apply typography in a dashboard is to think about it in terms of functions. Where do we use fonts in a dashboard layout? Why do we use them?

One of the most fundamental ways we use typography in a visual display of data is to enforce hierarchy.

There are many aspects to hierarchy, and we’ve already covered a few of them - layout placement, the use of colour, and now - typography.

We can do this by varying our fonts based on weight and size or even combining typography with colour and placement.

The Interaction Design Foundation has explained this really well in one image:

The accompanying article about visual hierarchy in design is also brilliant.

When it comes to a dashboard, there are a few basic places where we will use fonts.

Headings

Subheadings

Annotations in charts

Footer notes

Data Labels

Axis Labels

Callouts & Tooltips

UI elements like buttons, breadcrumbs and pathfinding cues

BANs (Big A** Numbers, or KPIs)

Smaller KPI indicators

Categories and subcategories in charts and tables

Numbers in tables

Filters

Once we know where we may use our chosen fonts, we can work our way into defining which of these deserve to occupy more space, be more prominent and better visible in our layout.

One good exercise is to organise the list above into order of importance. If you have to choose which of these elements should be seen by your audience, which ones would be first? Then next? And which ones would be the least relevant?

How would you organise your type scale?

Putting it all together

Let’s see some practical examples of all of these elements and take some tests.

Example 1:

First, let’s see what a chart looks like if we choose a condensed typeface (Alumni Sans). Readability proves to be a challenge, particularly in the footer note. Also, everything is bold in the hopes of making it more legible.

But when everything is bold, it is hard to tell what should be read first - there’s no hierarchy. We can try adjusting that first and see if it improves things.

Better, but still hard to read. Let’s try with a typeface that not only has a regular width but also a good x-height.

Yes, we can read it better now (typeface: Open Sans).

But the numbers look… strange? They don’t seem to be aligned! They are oldstyle and proportional, which makes comparing numeric labels an extra notch more difficult. Let’s adjust that.

But notice that, even though I am using the exact same sizes for both fonts, I now need more space for my labels, and my footnote occupies 2 rows.

From a stylistic point of view, I would like to keep the same kind of look - with narrower labels and the footnote in just one line. That’s why I chose a narrow typeface!

The good news is that we can achieve the same effect by adjusting the sizes of the new typeface - without compromising legibility.

But I think I can improve the hierarchy a bit more. The subtitle and the footnote are not as important as the title and the chart labels. I can subdue them in two ways: by selecting a thinner font weight, which can impact my readability at smaller sizes.

Or is it better to combine my use of font with my use of colour and choose a lower-contrast grey for those two elements? Notice how I can even make the extra small footer bold now - making it more legible - while the colour takes care of making the hierarchy clearer.

We were able to keep our stylistic choices, using a more legible font - even at smaller sizes!

Example 2:

Now, let’s look at the table below. It is set using the serif style typeface Georgia.

The first thing to notice is that everything is set in the same size (16pt) and all bold.

Let’s start by adjusting the font-weight.

Now, we can look at font size. We’ll reduce the table labels and content to 14pt.

But notice the old style and proportional numbers? In a table, they make for very difficult comparisons! Especially here, where we also have negative numbers, indicated by a minus symbol.

Even in the serif-style typeface, things are looking better! We can compare the figures more easily now. But what would it look like with a sans-serif typeface instead? Let’s try Lato:

Now, we can even work out to have the table content a bit smaller and still keep it legible, improving the hierarchy. Notice how much easier it is to skim through the values now!

I hope these examples can help you make better typography choices in your visualisations!

In the next issue, I’ll dive a bit deeper, creating a type scale to use in a dashboard and exploring the typeface options we have in Power BI and Tableau.

Until next time,

--T.

This is a repost of the Design Matters series I run as part of my newsletter, originally sent to my subscribers on 01 September 2023.

If you'd like what you read, consider subscribing so you can get all upcoming issues fresh when they're first out!

If you like what I share and would like to support my caffeinated habits, you can buy me a coffee!